Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

‘Most people thought I had lost my damn mind’

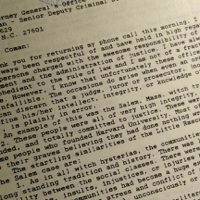

Portion of Dee Swain’s Jan. 12, 1993 letter to Attorney General’s Office on “the startling similarities of the Little Rascals case and the Salem” witch trials of 1692-93.

April 5, 2016

At a time when the Little Rascals claims were exposing widespread gullibility, a gritty band of doubters – e.g., Raymond Lawrence, Glenn Lancaster, Jane Duffield, Doug Wiik, Susan Corbett and Dee Swain – was desperately working to keep the defendants from being crushed by public opinion and prosecutorial coercion.

As treasurer for the Committee to Support the Edenton Seven, Swain distributed donations to defendants, facilitated the lowering of Scott Privott’s exorbitant bond and wrote an epic four-page (single-spaced!) letter educating the attorney general’s office on the errors of its ways.

How was it that a propane dealer in Washington, N.C., could see through the fog that engulfed so many professionals?

“It was obvious to me right away that it was hysteria,” he says. “I didn’t get involved until after (Bob Kelly’s) conviction – I had thought surely the jury would see through it….

“I’ve always been a skeptical person, someone who stands outside the box…. Most people thought I had lost my damn mind, defending ‘child molesters’…. I got anonymous phone calls….”

Swain is surprisingly generous to those who bought into the “satanic ritual abuse” stories elicited by prosecution therapists: “There aren’t any villains. They all acted in good faith. They were on a mission. They were going to be heroes….. You could see it all in ‘Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds’ (by Charles Mackay, 1841).”

And why does he think none have stepped forward a quarter century later to recant? “What they did was too terrible to admit to themselves.”

![]()

‘I knew right then it couldn’t be true’

Aug. 24, 2012

Aug. 24, 2012

My EDENTON7 license plate recently caught the eye of a former Little Rascals Day Care parent who left Edenton.

Although Maria – a pseudonym, as she still has family back home – withdrew her daughter from Little Rascals in 1989 after less than two months, it was because of outside circumstances, not because of any dissatisfaction with the care received. “It was a normal day care, clean and quiet,” she says.

The torrent of ritual-abuse rumors started soon after.

She was unsure what to make of it all until a former classmate, Dawn Wilson, was caught up in the dragnet. “Dawn had sat in front of me in high school,” she recalls. “She was quiet and shy, but she opened up to me about wanting to have a baby. She was a loving person. When I heard her name mentioned, I knew right then it couldn’t be true.”

Maria worked at Hardee’s, where she found it “painful to watch” Betsy Kelly’s parents, Warren and Alice Twiddy, being ostracized by their Wednesday-morning coffee klatch. “They were respected people…. She was the clerk of court. It was like she couldnt believe the town was doing this to her.”

Maria’s most surprising observation: “I think PBS (“Frontline”) changed the minds of a lot of people in Edenton. They saw how the gossip and innuendo had worked.”

How one journal editor went very, very wrong

Dec. 7, 2012

Dec. 7, 2012

Following up on Wednesday’s post:

Here’s how editor Gerry Fewster began his introduction to “In the Shadow of Satan: The Ritual Abuse of Children,” the still-unretracted 1990 special issue of the Journal of Child and Youth Care:

“Putting this issue together has been my most difficult Journal assignment…. It began as a fascinating prospect with little or no supportive documentation. As I discussed the concept with colleagues and friends the most unlikely doors began to open. Fragments of information – odd papers, crude and unfinished manuscripts, unsolicited telephone calls, personal revelations, and even photographs – began to appear….”

Dr. Fewster’s professional skepticism seems to have quickly yielded to those phantasmagoric “fragments of information.” He details an investigative process that….well, evaluate for yourself:

“Many times during the course of reading the material, I decided to quit. I found that I had neither the head nor the stomach for the task…. After spending many hours reading from the protective armor of the editorial role, I would feel physically ill. At first I attributed all of this to my reluctance to examine the depths of my own ‘shadow’ and urged myself on. Then, as my curiosity rekindled, I would shrink back in horror from the spectres of my own hidden motives and intentions….”

Dr. Fewster goes on to introduce his fellow contributors to “In the Shadow of Satan.”

Pamela S. Hudson, for instance, “provides an authoritative wide-angle perspective. Based upon clinical experience and the results of her own survey, the author identifies and discusses the most frequently reported symptoms and allegations surrounding ritual child abuse. Beyond the grisly nature of the content, this seasoned practitioner offers a wealth of insight for those who wish to know about satanic practices and better understand the terrifying experiences of children caught up in this vicious network.”

Hudson’s article isn’t available online, but fortunately is preserved in her subsequent book “Ritual Child Abuse: Discovery, Diagnosis and Treatment.” Here’s an example of the “wealth of insight” provided by “this seasoned practitioner”:

“The exceptional symptom in ritual abuse cases is the sudden eating disorder

demonstrated by these children. Besides being revolted by meat, catsup, spaghetti and tomatoes (which resemble organs), (cf., Catherine Gould) I had a case of a 20-month-old girl suddenly start to throw away her baby bottle. When she was older she said the perpetrator urinated into her baby bottle during his visits with her. Later, she spoke of witnessing the death of a baby girl….”

All this impressionistic pseudoscience could be written off as overreaching silliness, had it not contributed to the moral panic that swept up innocent victims such as the Edenton Seven. Isn’t it time for the editors at those professional journals that enabled the reign of error to at last set the record straight?

Faller, Everson resist trend toward skepticism

Sept. 24, 2012

Sept. 24, 2012

The February 2012 special issue of the Journal of Child Sexual Abuse is devoted entirely to “Contested Issues in the Evaluation of Child Sexual Abuse Allegations.”

Ritual-abuse holdouts Kathleen Coulborn Faller and Mark D. Everson use the issue to vigorously push back against calls for greater diagnostic skepticism.

The object of their displeasure is “The Evaluation of Child Sexual Abuse Allegations: A Comprehensive Guide to Assessment and Testimony” (2009), edited by the late Kathryn Kuehnle and Mary Connell. Contributors to the Kuehnle-Connell volume advocate more reliance on forensic science and less on “unverified methods or conjecture” of the kind that enabled prosecution of the Edenton Seven. By contrast, Everson and Faller can be counted on to stretch the bounds of prosecution-worthy evidence, from finding “clinical usefulness” in anatomical dolls to granting universal credibility to child-witnesses.

From Everson’s response in the journal:

“Many critics of current forensic practice (emphasize) specificity over sensitivity…. Specificity (minimizing inclusion of false cases) and sensitivity (maximizing inclusion of true cases) are counterbalancing indices of decision accuracy. Favoring specificity over sensitivity means that overdiagnosing (child sexual abuse) is considered a more serious concern than failing to substantiate true cases of abuse….”

Yes, I’ll admit it: I consider the perils of overdiagnosis – putting innocent people in prison – much worse than those of underdiagnosis – letting a possible abuser go free, at least temporarily. However much Everson and Faller might wish otherwise, our system of justice does stipulate “reasonable doubt.”

0 CommentsComment on Facebook